How Anxiety Affects Athletic Performance: Riding the Emotional Rollercoaster

This article delves into classic psychological theories explaining the complex relationship between anxiety and performance, providing insights and practical strategies athletes can use to thrive under pressure.

MENTAL SKILLS

5/30/202511 min read

In our previous article, we examined the crucial role emotions play in athletic performance, emphasising how understanding and managing emotions can substantially influence an athlete’s success.

It's as one LinkedIn user commented: "Emotions are how we achieve anything extraordinary in life."

We specifically defined key emotional terms, distinguishing between emotions, moods, and arousal, and introduced some foundational models that explain the connection between emotions and performance.

However, whether you've read that first article or are just joining us now, we're about to dive a bit deeper into one of the most powerful and influential emotions athletes experience: anxiety.

But why focus specifically on anxiety?

Because, in a nutshell, anxiety uniquely impacts athletic performance.

It often determines whether an athlete thrives under pressure or chokes at critical moments.

We know that anxiety, typically characterised by both mental worry and physical tension, can energise athletes to reach new heights or become a debilitating force that undermines years of training.

This reality, though, is also true of life in general (just as a side note).

So, to better understand and harness the power of anxiety for sports performance, we'll examine some established psychological theories, starting with the Inverted-U Hypothesis.

The what?

The Inverted-U Hypothesis: Finding Your Optimal Performance Zone

First introduced over a century ago by psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson, the Inverted-U Hypothesis remains foundational in sport psychology.

This theory suggests that the relationship between arousal (a physiological and psychological state of alertness or excitement) and performance resembles a bell curve, often referred to as the "Inverted-U."

What that means in simple terms is that at low levels of arousal, an athlete might feel too relaxed, resulting in suboptimal performance due to a lack of motivation or intensity.

But as arousal increases, performance typically improves, reaching an optimal midpoint.

Beyond this peak, however, further increases in arousal cause performance to deteriorate due to excessive anxiety, tension, or overstimulation.

In other words, it's like Goldilocks and the porridge - just perfect is perfect.

Think of a sprinter poised at the starting blocks...

If they're overly relaxed, they risk lacking explosive power or quick reaction time when the gun fires, which is crucial over short distances, such as 60m or 100m races. There's no time to make up for it.

Conversely, if you're overly anxious, you might jump the gun, react poorly, or become too tense to sprint effectively.

And in modern-day sprinting with the one false-start-disqualification rules, that can be disastrous.

This theory argues that optimal performance occurs when the sprinter achieves the perfect balance, being alert and energised, yet controlled and focused.

But, therein lies a challenge for athletes and coaches alike.

Since athletes differ, the optimal (performance) point varies significantly across different individual athletes AND also across different sports.

For instance, a powerlifter or a football player often thrives under conditions of higher arousal and excitement, using adrenaline and intense energy to enhance their power output.

In contrast, an archer, golfer, or gymnast typically performs best with lower arousal levels, relying on calmness and precision rather than heightened energy.

Check lane 8 (South Africa's first leg runner) in the video below -- a classic example of where nerves were slightly more than control and balance. He fixed it on the second attempt.

So, why is this important?

In essence, understanding this relationship mentioned above can help athletes identify their unique "sweet spot" for arousal, enabling them to tailor their mental and physical preparation strategies to achieve peak performance consistently.

And to make sense of the graph above, think of it as a visual map of how your body and mind respond to pressure.

On the left, you're too chilled, maybe you're flat, unmotivated, or just not locked in.

On the far right, you're too fired up, tight muscles, racing thoughts, and poor decision-making start to show up.

But right in the middle is the peak zone that's your personal performance sweet spot.

So, your goal as an athlete is to figure out where that zone is for you and learn how to get yourself there before training sessions or big games consistently.

What This Means for You

If you're an athlete, start paying attention to how your body and mind respond in training and competition.

Do you feel too relaxed and sluggish before games?

Or are you often too hyped and jittery, making mistakes under pressure?

Reflecting on your own patterns of arousal can help you identify when you're in the zone and when you're off.

Once you know your optimal arousal state, you can begin to experiment with strategies to either raise or lower your arousal to hit that sweet spot.

This might include pre-game routines, breathing exercises, music, visualisation, or motivational cues.

Coaches can also support athletes by recognising when arousal levels are out of balance and guiding them back toward their personal performance peak.

Now, crucially, finding your ideal arousal zone isn’t a one-time task; it’s a skill that improves with self-awareness, honest reflection, and deliberate mental training.

OK, let's now go even further...

Beyond the Basics: Drive Theory and Reversal Theory

While the Inverted-U Hypothesis introduced the idea that performance peaks at an optimal level of arousal, it doesn't explain every scenario.

Sometimes, performance continues to improve even as arousal intensifies, particularly for athletes with a high tolerance for pressure.

At other times, two athletes with identical arousal levels may experience completely different outcomes.

That is where other theories help fill the gaps.

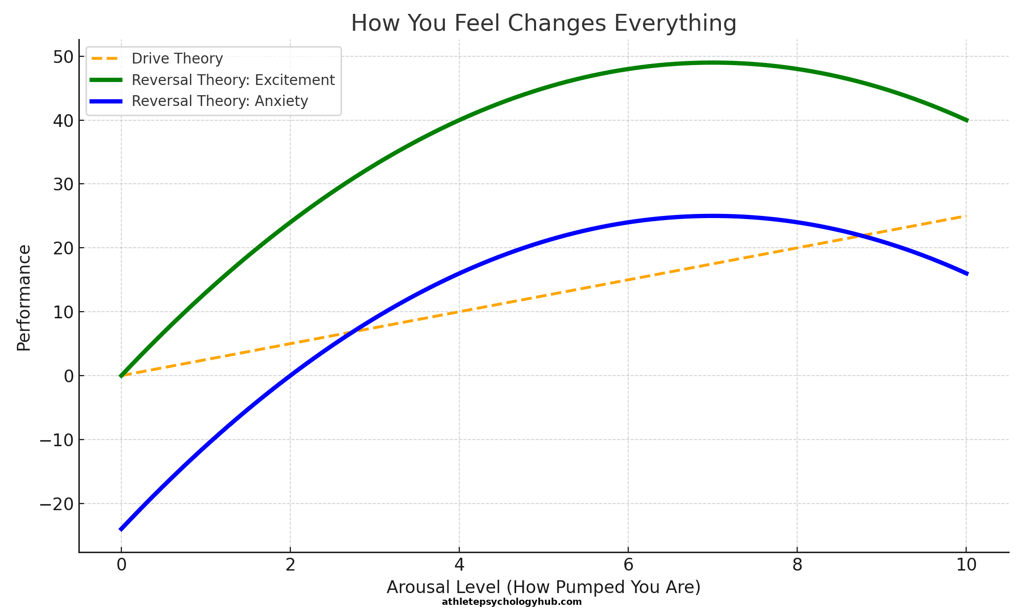

For instance, the Drive Theory

This theory, initially proposed by Hull and expanded by Spence and Zajonc, suggests a linear relationship between arousal and performance.

In other words, more arousal equals better performance.

And this idea holds especially true for simple or well-practised tasks.

For instance, in high-pressure situations, an experienced athlete may perform even better because their dominant responses, ingrained through repetition, take over automatically.

Think of a seasoned kicker taking a penalty in front of thousands: their arousal might be high, but their training allows them to execute flawlessly.

However, Drive Theory has its limits.

It struggles to explain choking and why some highly skilled athletes underperform in high-stakes moments.

This is where Reversal Theory adds a valuable perspective.

According to Reversal Theory, it’s not just about how much arousal you experience, but how you interpret it.

For example, the same rapid heartbeat and tension can feel exciting to one athlete, and terrifying to another.

In psychological terms, one sees it as a challenge, the other as a threat.

The magic, however, lies in your ability to “flip the switch” and reframe (or appraise) anxiety as excitement, turning nerves into a performance enhancer instead of a roadblock.

So,

What This Means for You

If you're an athlete, pay attention not only to your physical state but also to your mindset.

Next time you feel nervous before a game, ask yourself: Is this fear, or is this fuel?

That simple mental shift can change everything.

And with practice, you can learn to reinterpret pressure as a signal that you’re ready, not that you’re about to fail.

Coaches can also help athletes reframe anxiety by reinforcing phrases like “This means you care” or “Your body’s getting ready to perform.”

It’s a simple tweak in language, but it can recalibrate the athlete’s internal narrative and help performance follow suit.

What You're Looking At

Drive Theory (yellow line) is shown as a straight, rising line (more arousal = better performance).

Reversal Theory is illustrated with two curves: one where arousal is interpreted as excitement (green line: better performance), and another where it's interpreted as anxiety (blue line: lower performance).

Multidimensional Anxiety Theory: Dissecting the Layers of Stress

Now, so far, we’ve looked at how arousal and performance interact and how our interpretation of that arousal can shift outcomes dramatically.

But to coach or train this well, we need to zoom in even further.

We need to ask: What exactly is anxiety made of?

And do all types of anxiety affect performance in the same way?

This is where the Multidimensional Anxiety Theory becomes incredibly useful.

Instead of treating anxiety as a single force, this model separates it into specific components, giving us more precise levers to work with.

It suggests that not all anxiety feels the same, and it doesn’t affect performance the same way either.

By the late 1980s, sport psychologists began moving beyond the idea that anxiety is a single experience.

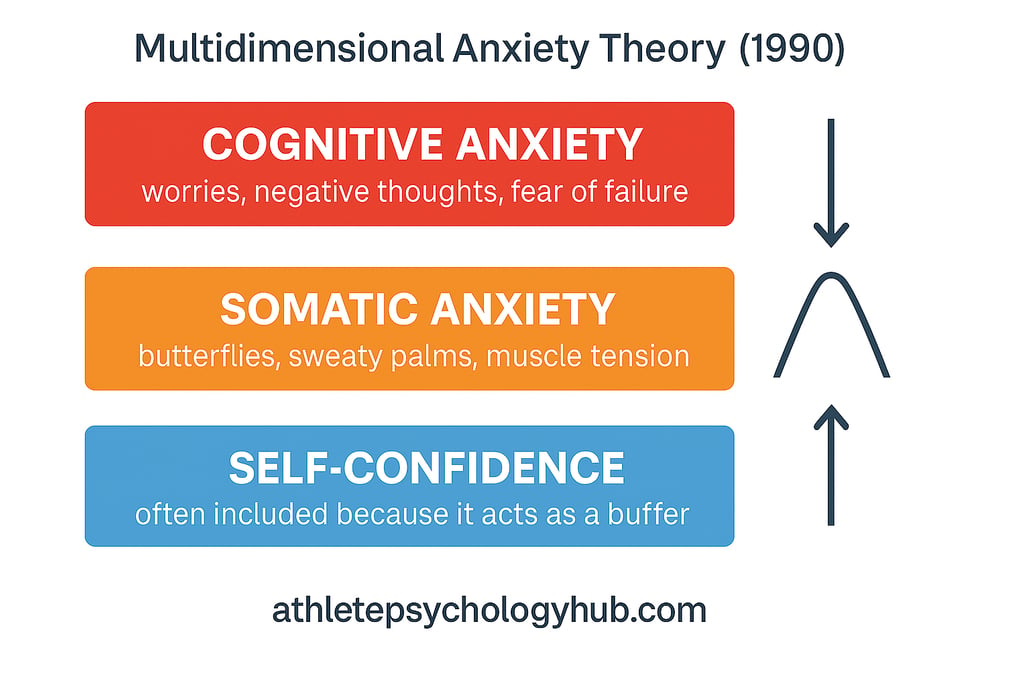

One of the most practical models to emerge from this shift is Martens’ Multidimensional Anxiety Theory (1990), which breaks anxiety into two main types: mental and physical.

This is what it looks like:

Cognitive Anxiety is what happens in your head: worry, fear of failure, overthinking, and worst-case scenarios.

Somatic Anxiety is what happens in your body: a racing heart, butterflies in your stomach, sweaty palms, tight muscles.

Self-confidence isn’t anxiety itself, but it’s often added into this model because it can protect you from the negative effects of worry. Confidence acts like a mental buffer, keeping thoughts in check and letting physical energy work for you, not against you.

Furthermore, these pieces don’t affect performance equally.

It argues that:

Cognitive anxiety usually has an adverse linear effect on performance. The more you worry, the worse you tend to do.

Somatic anxiety follows the same inverted-U shape we discussed earlier in that too little or too much can hurt, but a moderate level can help.

So, imagine a gymnast about to compete on beam.

Her body is warmed up and ready (somatic), but her mind is filled with doubts like "What if I fall again?" (cognitive).

That mental tension can sabotage her performance, even if her skills are sharp.

On the flip side, an athlete with a similar level of physical anxiety but a calm, confident mindset is more likely to execute cleanly, stay present, and recover if something does go wrong.

Now, interestingly, research also shows that self-confidence plays a protective role.

Athletes with high self-confidence tend to experience less cognitive anxiety, and even when they do feel nervous, it doesn't derail their performance as easily.

So, definitely something to consider developing.

What This Means for You

Ultimately, this model reminds athletes to take a two-pronged approach: manage your body and master your mind.

If your thoughts are spiralling into worst-case scenarios before a competition, pause and reframe.

Learn to practice self-talk strategies that replace fear with focus.

Short phrases like “I’ve prepared for this” or “One moment at a time” can redirect runaway thoughts.

Coaches should also help athletes craft personal mantras during training that become automatic under pressure.

If your body feels too tense, incorporate breathing techniques or progressive muscle relaxation into your routine.

And remember: building self-confidence through consistent training and small wins is one of the most effective ways to guard against anxiety’s negative effects.

As a coach, start by having athletes reflect weekly on progress, however small.

Coaches can also model belief, meaning what you consistently affirm (e.g., “You’ve handled bigger situations than this”) becomes part of the athlete’s internal voice.

It is one of the most effective ways to guard against anxiety’s negative effects.

The more confident you are, the less room anxiety has to take over.

Now, let’s explore the model that captures the most dramatic form of performance breakdown.

Catastrophe Theory: When It All Falls Apart

While earlier models help us understand steady changes in performance, Catastrophe Theory (Fazey & Hardy, 1988) introduces a powerful warning:

When cognitive anxiety is high, even a small spike in arousal can lead to a sudden and dramatic performance collapse.

According to this model, this isn't a gradual decline; it's a cliff.

In other words, if you're both highly worried and physically pumped up, your performance doesn’t just dip, it can fall apart completely.

For instance, a tennis player who has held their own throughout a match may suddenly double-fault multiple times in a row under pressure.

Or a rugby kicker might shank an easy conversion after two previous misses.

This is what choking under pressure often looks like.

Catastrophe Theory suggests there’s a tipping point: athletes with high cognitive anxiety are much closer to that edge.

And the only way back is to reset and calm down significantly before attempting to climb back up.

I've seen this firsthand, which is why I started teaching rugby players my Traffic Light System - it's a gradual process from potential performance implosion back to taking control and achieving flow again.

It's a climb.

So,

What This Means for You

If you're someone who tends to worry a lot before games, you need to manage both your mental and physical arousal.

Mindfulness, breathing, slowing your heart rate, and grounding exercises are all tools that can keep you from crashing.

And for coaches, this theory is a reminder: yelling or overhyping a nervous athlete might backfire.

The key insight here is that it's not just about staying below your personal anxiety threshold.

You need reliable tools in high-pressure moments, such as the 5-4-3-2-1 sensory scan or rhythmic breathing, to slow your heart rate.

For coaches, this means creating calm spaces between plays, giving clear instructions, and not flooding anxious athletes with information.

A simple phrase like “Focus on the next task” can become a lifeline in high-anxiety situations.

Ultimately, in my experience, it’s about building awareness and skills to keep your arousal in check, especially in clutch moments, when the difference between rising and collapsing is paper-thin.

Regulating Emotions in Real Time

All these models point to a central truth: it's not about eliminating anxiety, it's about working with it.

At the end of the day, athletes need systems to assess, manage, and redirect emotional energy.

That's the heart of it.

Forget the theories if you want, but remember that!

And one proven framework is the use of mental resets.

After a mistake or a spike in stress, use a 3-step reset (for example):

Recognise your state ("I'm too pissed-off right now" or "I'm spiralling")

Refocus using a cue word or breath (e.g., one deep exhale and say, "next task")

Re-engage with the present moment—what’s happening now (must happen now), not what just happened.

Also, in training, simulate pressure moments.

I'm a proponent of pressure training.

Add consequences to drills.

Use a scoreboard.

Use a timer.

Create fatigue before skill execution.

Then teach athletes to manage their emotions through it.

This builds automatic emotional resilience, much like lifting builds physical strength.

And coaches can further support this by modelling calm under pressure and rewarding emotional regulation, not just physical execution.

For example, praising publicly how an athlete refocused after a mistake rather than only celebrating the next point scored.

What you train under pressure is what shows up under pressure.

For most, emotional control is not a gift or talent; it’s a practised skill set.

Final Thoughts: Building a Foundation for Control

Anxiety is part of sport. It’s part of being human.

But the difference between those who crumble under pressure and those who rise is rarely about talent; it's about how well you prepare for those emotional moments.

This article has unpacked some of the classic models that explain how anxiety impacts performance.

From the Inverted-U to Catastrophe Theory, we’ve seen that the goal isn’t to avoid anxiety but to understand it, manage it, and ultimately use it.

But these models aren’t just theory.

They should guide what you do in training, how you reflect after performances, and how you prepare emotionally for competition.

In Article 3, we take the next step by looking at practical tools for emotion regulation and reframing anxiety in real time.

You'll learn how to convert anxiety into energy, sharpen your mindset under stress, and coach these strategies into everyday routines.

Whether you're an athlete, coach, or parent, this final piece will show you how to turn all this insight into action.

Mental Skills Training

Equipping athletes with the practical psychological tools they need to gain the edge—on and off the field.

Free Guide: The Mental Edge

contact@athletepsychologyhub.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Support

Build confidence, focus, and mental toughness with the 5-step system used by top athletes.