Understanding Emotions in Sport: Models, Impact, and Insights

This is the first article in a three-part series on core emotion models and their relationship to sports performance.

MENTAL SKILLS

5/19/202514 min read

Why Emotions Matter in Sport

Every athlete knows the feeling...

The surge of adrenaline before a race.

The sting of a mistake.

The pure joy of crossing the finish line first.

These aren’t just side effects of playing sport, they’re central to it.

For,

Emotions drive performance, shape decision-making, and influence how we show up, both in competition and in training.

In sport, where outcomes are uncertain and stakes feel high, emotions often run the show.

I used to say to athletes, it either helps or hurts you on the field, so make sure it helps.

Psychologists often call sport a “hotbed for emotion” because athletes are constantly pursuing meaningful goals under pressure and scrutiny, whether it’s from spectators, sponsors, coaches, family, or their own expectations.

We care about doing well, so we feel intensely.

“You know what we worry about? Things we care about. I didn’t get nervous making breakfast this morning.” — Jonah Oliver, sport psychology expert

Even elite athletes experience intense emotions; I would argue that, due to the pressure, they may feel them even more intensely.

The difference is that they’ve learned to use those emotions instead of being used by them.

Take nerves, for example.

One person’s anxiety is another person’s excitement.

Physiologically, they look almost the same (elevated heart rate, faster breathing), but the mindset around them can mean everything.

In fact, research shows that how you interpret your emotions (we call it cognitive appraisal or framing), especially in high-pressure moments, can directly impact your performance.

One athlete might see nerves as a warning sign, while another sees them as a green light to perform optimally.

And that framing can be the edge that separates choking from clutch.

Now, this article is the first in a three-part series that breaks down the science and psychology behind emotions in sports.

We’ll start by explaining how emotions work, looking at the different ways psychologists model them, how they relate to performance, and what elite performers tend to get right.

Later in the series, we’ll focus on anxiety, arguably the most common (and misunderstood) emotion in sport, and wrap up with practical strategies athletes, coaches, and even parents can use to manage emotions under pressure.

So, whether you’re a teenager lining up for your first big race or a seasoned pro wanting to do well this season, learning how to understand and work with your emotions is a crucial and competitive skill to get good at.

Mood, Emotion, and Arousal: What’s the Difference?

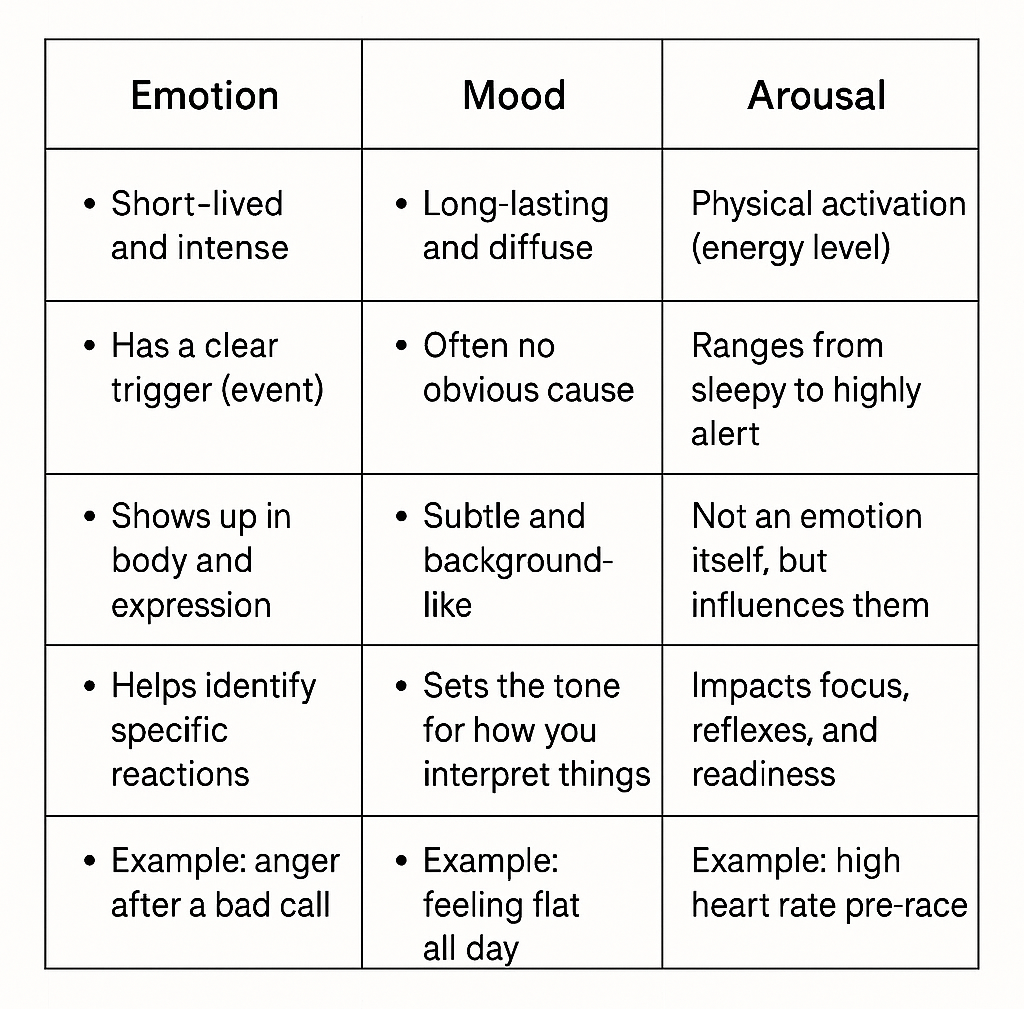

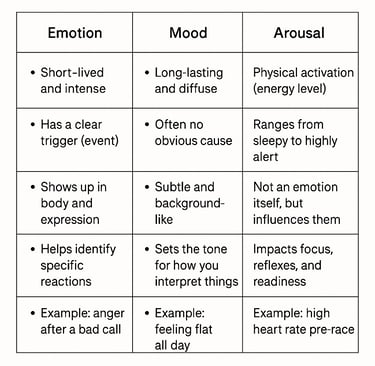

In everyday conversation, we often use the words mood, emotion, and arousal interchangeably.

But in psychology, and especially in sport psychology, they’re not the same thing.

And understanding the difference can help athletes figure out what they’re feeling and why it matters.

Let’s break it down:

Emotion

Emotions are typically short, sharp responses to something specific: a bad call, a personal best, a surprise win, a missed goal.

They tend to be intense, brief, and usually have a clear cause.

You feel anger because of an unfair tackle.

You feel joy because you nailed a move..

Emotions also often show up in your body, too, flushed cheeks, shaky hands, butterflies, or a rush of energy.

And in sport, emotions tend to rise and fall fast.

You might go from frustration to focus in under a minute.

That’s why recognising what triggered an emotion, and how you react, can make or break your next play.

Mood

Moods are more like the emotional “weather” you’re walking around in.

They last longer, can be harder to pinpoint, and don’t always have a clear trigger.

You might just wake up feeling off or great, without knowing why.

And that baseline mood can colour how you interpret everything else.

For example, if you’re in a low mood, a teammate’s feedback might feel like criticism.

But if your mood is up, you might take the same comment as encouragement.

In short, in sport, mood can affect energy, motivation, and even injury risk over time.

That’s why managing mood, especially during long training blocks or recovery periods, is just as crucial as managing skill and fitness.

Arousal

Arousal, however, typically refers to your physiological activation level: where your body is on the scale from dead asleep to highly alert and amped up.

It’s not an emotion in itself, but it plays a big part in how emotions feel.

For instance, you can be highly aroused and feeling positive (like excited), or highly aroused and feeling negative (like anxious or panicked).

On the flip side, low arousal might be experienced as calm and focused, or flat and disengaged.

Arousal also tends to affect reaction time, coordination, decision-making, basically, all the things that matter in competition.

So, finding your ideal arousal level is a big part of performance.

And what’s ideal for you might not be for someone else.

For example, a tennis player might need to dial their energy up; a rugby player might need to bring theirs down to stay composed.

How Psychologists Understand Emotions: Two Big Lenses

If you want to improve how you handle emotions in sport, it helps to first understand how psychologists make sense of emotions in the first place.

Over the years, researchers have developed two main ways of thinking about emotion: one sees emotions as distinct categories, and the other treats them more like coordinates on a map.

Both are useful, and both show up often in sport psychology.

1. The Categorical Approach: Naming the Feeling

The first approach is called categorical or discrete emotion theory.

It’s probably the most familiar because it matches how we naturally talk about our feelings.

We say things like “I felt angry,” or “I was nervous,” or “That moment filled me with pride.”

This model treats emotions like basic ingredients, distinct, recognisable, and with a clear flavour.

Psychologist Paul Ekman is one of the best-known voices in this space.

His research showed that people across cultures recognise a small set of “basic” emotions just by looking at facial expressions: happiness, anger, sadness, fear, disgust, and surprise.

These are considered universal, hard-wired into us, regardless of language or culture.

In sports, you also see these show up all the time...

The clenched jaw after a missed opportunity.

The raised arms and beaming smile after a big win.

The wide-eyed hesitation just before the opening whistle.

These expressions aren't just body language; they’re evidence that emotion is happening fast, often before we’re even aware of it.

Another important figure in this space is Richard Lazarus, who added a powerful insight: it’s not just the event that causes emotion, it’s how we interpret that event.

This is known as appraisal theory.

Take two athletes who both fall short in a race.

One feels ashamed and defeated, thinking, “I’ve let everyone down.”

The other feels motivated and determined: “That wasn’t my best, but I know how to fix it.”

Same result, completely different emotions, simply because they judged the meaning of the event differently.

Lazarus argued that every emotion arises from a kind of quick internal conversation: Is this good or bad for me? Can I handle it? Is someone else to blame?

Depending on the answers, we generate an emotional response.

And again, in sport, these appraisals happen all the time, often in milliseconds, and they’re powerful.

Essentially, what we know is that athletes who can slow down, reframe (or re-appraise) a situation, or shift their interpretation have more control over their emotions.

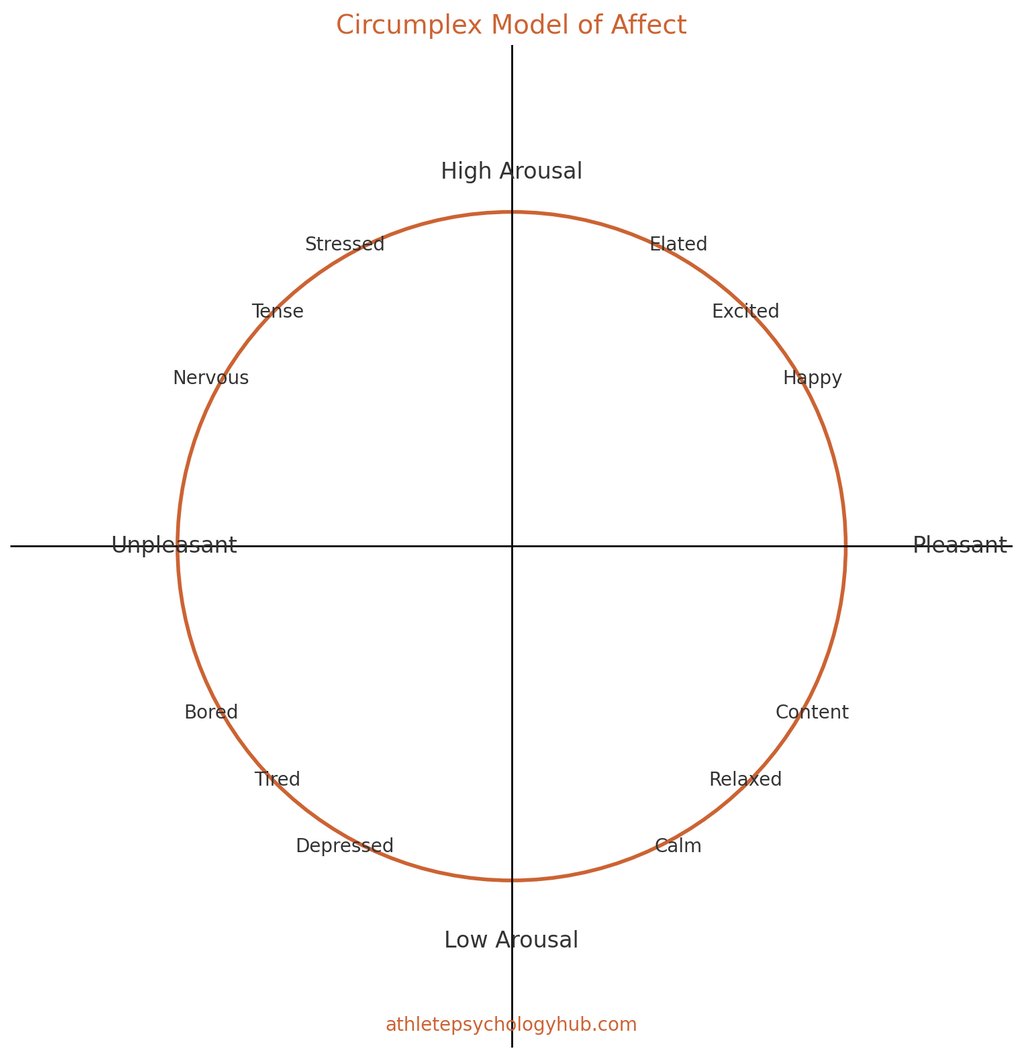

2. The Dimensional Approach: Mapping the Feeling

While the categorical model focuses on naming specific emotions, the dimensional approach zooms out and asks: How do these emotions relate to each other?

Instead of dividing emotions into categories, this model maps them along two key axes:

Valence (pleasant to unpleasant)

Arousal (low energy to high energy)

If you imagine a graph or a circle, every emotion sits somewhere on this two-dimensional plane.

What Peak Performance Feels Like: Two Models That Map Emotion in Sport

We often talk about performance (and review it) in terms of physical metrics, speed, strength, and reaction time.

But some elite athletes and coaches know that mental and emotional states are just as measurable, even if not as obvious.

And to help, two well-known models in sport psychology give us powerful tools to understand how emotional states relate to performance: IZOF and the Iceberg Profile.

IZOF: Finding Your Emotional Sweet Spot

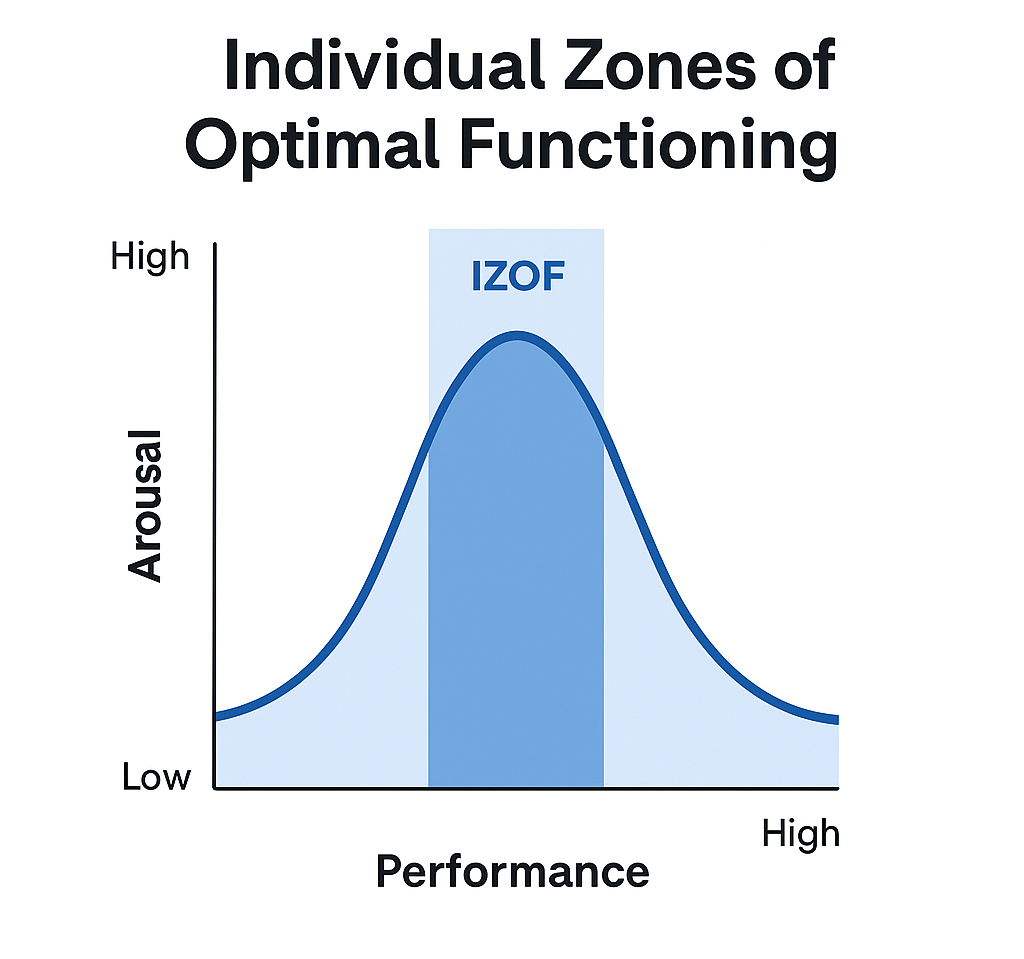

The Individual Zones of Optimal Functioning, or IZOF, was developed by Russian sport psychologist Yuri Hanin.

His idea was refreshingly simple, and quietly revolutionary: There is no single “right” emotional state that leads to peak performance.

Instead, each athlete has their own unique emotional zone where they perform at their best.

One athlete might compete best when they’re amped up, aggressive, and fired with adrenaline.

Another might need to feel calm, focused, and slightly detached to get into the zone.

Both are valid.

Hanin’s insight was that great performance happens not because of one universal emotional formula, but because an athlete is operating within their own ideal range.

Now, this model sits somewhere between the categorical and dimensional theories we discussed earlier.

It recognises that specific emotions matter, but so do how intense they are and whether they’re pleasant or unpleasant.

Hanin found that athletes tend to perform their best when their emotions are in a familiar, preferred range, which might include a mix of pleasant and unpleasant feelings.

For example, a rugby player might need a bit of controlled aggression, while a swimmer might need to feel confident but calm.

The practical takeaway is huge: instead of trying to “stay calm” or “get pumped” based on what works for someone else, the smart move is to discover your IZOF.

And that starts with reflection.

Look back at your best performances,

What did you feel just before and during?

Were you tense or relaxed?

Confident?

Fired up?

What about your worst performances?

What emotional state were you in then?

Once athletes know their zone, the goal becomes clear: recreate that emotional state on demand.

I sometimes refer to this as modelling your ideal performance self (IPS).

That’s where pre-performance routines, breathing techniques, music choices, visualisation, and coaching cues come in.

They’re all tools to help an athlete dial into the emotional state that works for them.

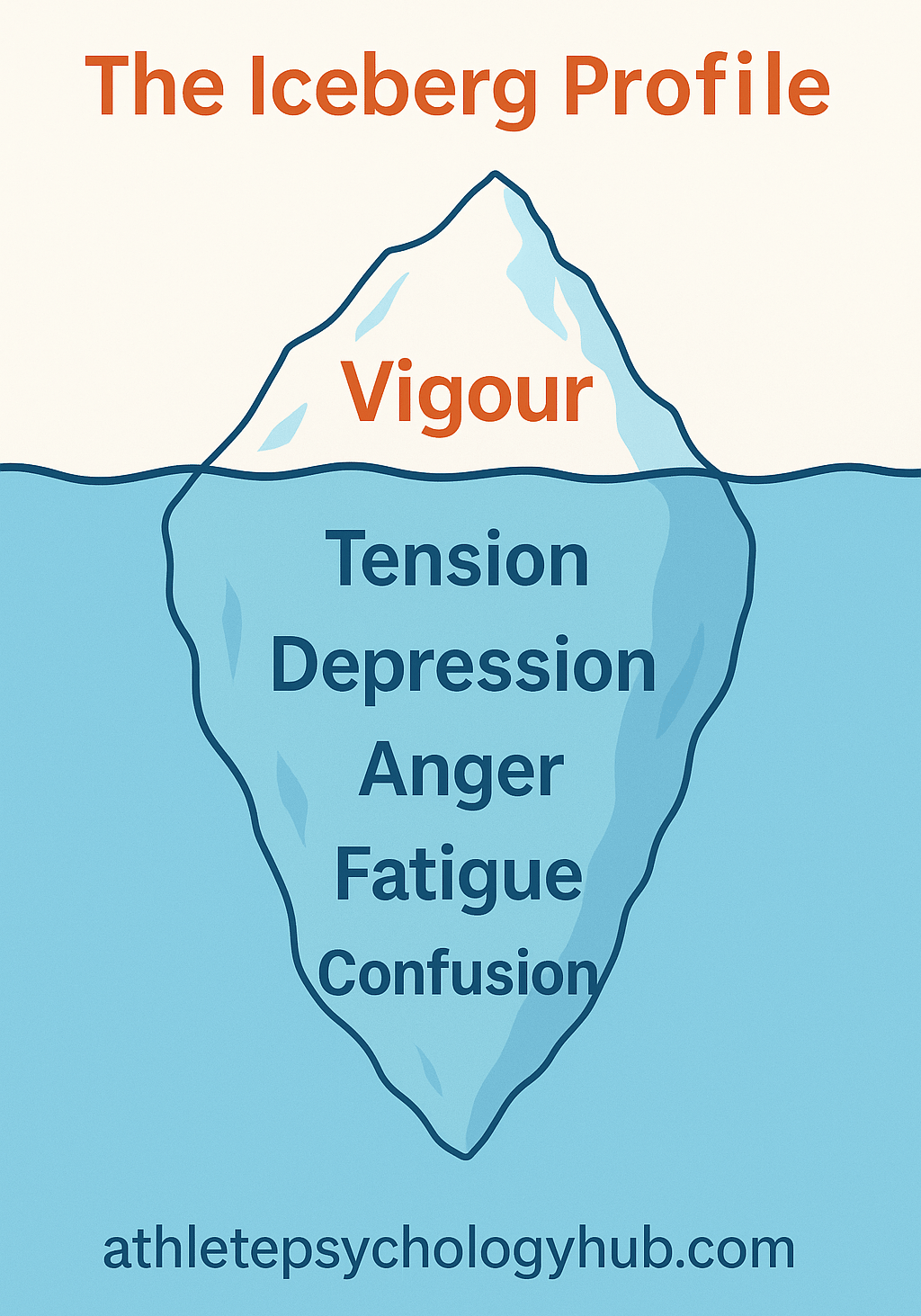

The Iceberg Profile: What Champions Tend to Feel

Another model that’s shaped how we think about mood and performance is Morgan’s Iceberg Profile, developed by psychologist William Morgan in the 1980s.

He wanted to understand how mood states, not just momentary emotions, affected athletic performance.

So he started testing athletes with a tool called the POMS (Profile of Mood States), which measures six key areas: tension, depression, anger, fatigue, confusion, and vigour.

And when he charted the results of elite athletes, something fascinating emerged.

Successful athletes tended to score high in vigour (energy, positivity) and low in the other five negative moods.

When graphed, their scores looked like an iceberg, one tall peak (vigour) above the surface, and the rest sitting low below the waterline.

That’s where the term “Iceberg Profile” came from, and it’s still used today as a quick mental snapshot of an athlete’s emotional health and readiness.

But what does it mean in practice?

If you’re heading into a key competition with high levels of fatigue, tension, or confusion, and low vigour, it may be a warning sign that something’s off.

Maybe you’re overtrained, under-recovered, or mentally drained.

Coaches and sport psychologists often use this model as an early detection system, helping athletes catch a slump before it turns into burnout.

But the flip side is also true: if your mood profile shows low negativity and high vigour, chances are you’re in a good place to compete.

You don’t need to feel euphoric, just stable, energised, and focused.

That combination tends to correlate with strong, consistent performances.

Using Both Models to Your Advantage

IZOF and the Iceberg Profile work hand-in-hand.

IZOF is personal and performance-focused; it’s about your ideal emotions before and during competition.

The Iceberg Profile is more general and health-oriented; it gives you insight into how your mood is trending over days or weeks.

But together, they remind us that emotions don’t just “happen” to athletes; they can be tracked, shaped, and optimised.

Yes, it's true that you can’t always control what kind of day you’ll have on the sports field.

But with the right awareness and tools, you can give yourself the best shot at showing up emotionally prepared, not just physically ready.

And when those two align, higher performance tends to follow.

Wrapping It All Together

By now, it should be clear that emotions are not a side note in performance; they’re centre stage.

Whether it’s the edge of anxiety that sharpens focus or the calm that anchors you in chaos, your emotional state is a core part of your competitive identity.

The IZOF model gives us a framework to stop guessing and start noticing patterns.

When athletes understand which emotional states consistently bring out their best (and worst), they can begin to train their emotional regulation just as they would physical conditioning.

And the interactive tool you just used is a first step, a way to identify your Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning.

But it’s not a one-and-done.

Peak performance is also built on awareness, feedback, and repeated reflection.

So,

In Part 2: Training Emotional Control Under Pressure

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll shift gears.

Now that you (hopefully) know your ideal performance zone, I’ll show you how to:

Train real-time emotional regulation under pressure

Build pre-competition routines that actually work

Use stress, nerves, and energy spikes to your advantage

Avoid the mental traps that sabotage performance

I’ll also include practical drills that coaches and athletes can use immediately, as well as guidance on how to integrate these into training without compromising physical intensity, which is also essential.

For now, though,

Remember: physical readiness gets you to the start line.

Emotional control gets you to the podium.

Let’s train both.

For example, joy would be high arousal and pleasant, like scoring a winning goal in front of a cheering crowd.

Anger is also a high-arousal arousal, but unpleasant.

Sadness is unpleasant and low arousal.

Calm is low arousal and pleasant.

This is often called the circumplex model of affect, and it gives athletes and coaches a practical framework.

Not everyone needs to say, “I feel irritated” or “I feel anxious.”

Sometimes it’s enough to ask: “Am I up or down right now? And does it feel good or bad?”

That alone can help you get your bearings.

Now, in a performance context, this is gold.

Let’s say you’re feeling flat and detached during warm-up.

That’s low arousal and possibly unpleasant; maybe it means you need to fire yourself up.

On the other hand, if you’re jittery and tight before a precision event like archery or golf, you might be in the high-arousal-unpleasant zone, too much tension, not enough control.

The goal then becomes moving closer to the pleasant and productive quadrant, maybe something like energised focus or calm confidence.

Why Both Models Matter in Sport

It's important to know that these two models aren’t rivals.

It's not one against the other.

They’re essentially two different lenses, and when you combine them, you get a more complete picture.

The categorical model helps with labelling and language: “This is anxiety, this is frustration, this is pride.”

That kind of clarity is useful in conversation, journaling, or coaching sessions.

It also reminds us that each emotion has its own effect.

Anger might fuel a powerlifter but wreck a gymnast’s fine control.

Joy might increase openness and creativity, but too much excitement can break focus.

The dimensional model helps with self-regulation: “Where am I on the map, and where do I need to go?”

It allows athletes to tune into their internal state and make small adjustments.

It’s especially helpful when the emotion feels mixed or hard to name, which is common in sport, where you can feel nervous and excited at the same time.

This is also where sport psychology starts to get really actionable.

When you know how your emotional state lines up with your ideal performance state, you can work toward managing emotion instead of trying to eliminate it.

And that’s the real takeaway: emotions aren’t distractions to push away. They’re feedback.

The goal isn’t to be emotionless; it’s to become more emotionally fluent.

Because athletes who can recognise, adjust, and harness their emotions don’t just cope better under pressure, they compete better, too.

How Emotions Show Up on the Field (or Court, or Track…)

So, hopefully by now, it’s clear that emotions are more than just background noise in sport; they shape how athletes prepare, how they compete, and how they recover afterwards (or from setbacks like injuries).

However, to truly understand their impact, it also helps to zoom in on a few specific moments that most athletes will recognise instantly.

The Pre-Game Jitters

You’re standing behind the blocks.

Or lacing up in the locker room.

Or pacing the sideline before kickoff.

Your heart is racing.

Your stomach feels like it’s full of bees.

You’re wired.

This is a classic example of high arousal, but what emotion is it?

Well, that depends on your mindset.

If your inner voice is saying, “I’m not ready… I hope I don’t blow it,” you’re probably experiencing anxiety.

But if you’re thinking, “This matters — let’s go,” the same physical symptoms might feel like excitement or readiness.

This moment is where appraisal comes into play.

Your body’s doing the same thing either way; it’s the meaning you attach to it that shapes the emotion.

And that emotion will affect how you start the game.

And we know that athletes who interpret their nerves as helpful tend to perform better.

Those who see it as panic or unpreparedness tend to tighten up.

The Angry Response

You and I both know that sport isn’t always fair.

A ref misses a foul or makes a shocking call.

A teammate lets you down.

The opposition taunts you.

Suddenly, you feel heat rise in your chest, your face flush, your body tense.

That’s anger, one of the most misunderstood emotions in sport.

Some athletes use it well.

They channel the energy into sharper focus or harder play.

But others get thrown off, lose their cool, lash out, lose discipline, or spiral into poor decision-making.

Again, the emotion itself isn’t the problem.

It’s what you do with it.

Knowing how to reset after an emotional spike, through a breath, a routine, or a quick mental cue, is a key skill to master.

And, like all skills, it can be developed and trained.

The Joy After a Win (or the Drop After a Loss)

When you’ve given everything and it pays off, the emotional payoff can be massive.

That’s not just pride or happiness, it’s a full-system reset.

Your energy suddenly lifts (even though you just played an 80-minute rugby game), your body language opens, and your confidence soars.

Positive emotions like joy, pride, and relief can have a contagious effect on team culture and self-belief.

But it’s also possible to lose focus when riding too high.

Teams that celebrate too long often get scored on immediately afterwards.

So, the emotional high needs to be balanced with the ability to re-engage quickly.

This point here alone is something I've tried to get players to understand so many times, yet many have missed it and often paid the price.

On the flip side, after a loss or poor performance, the emotional slump is real.

Athletes may feel disappointment, frustration, or dejection.

These are lower arousal, negative valence states, the emotional equivalent of heavy legs.

They can linger and affect the next session or game if not addressed.

That's when we start saying that losing, like winning, can become a habit.

But this is also why emotional regulation, knowing how to acknowledge, process, and shift emotional states, is so crucial.

Because ignoring emotions doesn’t make them go away.

Working with them does.

Mixed Emotions Are Normal

One final point worth mentioning here is that most emotional moments in sport aren’t clean.

They’re layered.

A sprinter might feel relief and disappointment in the same breath.

A footballer might be furious about a call but still locked in and ready.

A young athlete might feel proud of a personal best and still wish it had placed higher.

Now, mixed emotions don’t mean something’s wrong.

They simply mean you’re human.

But the goal is never emotional perfection, it’s emotional awareness.

Which brings us to two tools that can help athletes and coaches track and work with those feelings over time: IZOF and The Iceberg Profile.

These models can also help explain why emotional state matters and how athletes can find their own personal formula for performing at their best.

Want to Know What Emotional State Helps You Perform at Your Best?

I created the IZOF Performance State Assessment (below), which you can take for free, to provide personalised insight into your ideal performance zone.

You simply choose your best answers and see what result is kicked out.

You can then use that result to discuss with your coach, mental skills coach, or teammates to construct a strategy that utilises the information effectively moving forward.

Mental Skills Training

Equipping athletes with the practical psychological tools they need to gain the edge—on and off the field.

Free Guide: The Mental Edge

contact@athletepsychologyhub.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Support

Build confidence, focus, and mental toughness with the 5-step system used by top athletes.